Speech for the Criminal Community Justice Board (CCJB) meeting

Hamed Farmand, president of Children of Imprisoned Parents International

Thank you so much for having me. It is my honor to talk with you about one of the most vulnerable populations; children with incarcerated parents.

Last summer, for the second time, I attended a summer camp. That camp was designed by the United Methodist Church, for children whose parents are in prison. It was held in the Shenandoah Valley. My role was to be a mentor of two boys, one of whom, Arthur, was 11 years old. (Name has been changed to protect his privacy). Arthur and I created quite a close relationship, and I make sure to continue to keep in touch with him and his grandmother, who is also his caregiver. Arthur trusted me, and one day he told me that in the next year – this coming summer – his mother (who was in prison for 5 years) will be released. I lost the rest of our conversation, because I recalled my own personal experience. When my mother came home from prison after 5 years, I was exactly his age.

Since 2012, two years after I immigrated to the United States, I started my research about the effects of parental incarceration on children. As part of my research, I read some non-academic sources, which had been collected nationwide; authentic stories from children with incarcerated parents. “All Alone in The World,” by Nell Bernstein, and “What Will Happen to Me,” by Howard Zehr, are just two of those documents. Through these stories and my research, I realized that even though my mother was arrested due to her human right activities, and that just because it happened in a different country (with a different culture and more than 3 decades ago), there are more similarities than differences between my own experience and Arthur’s. In fact, Arthur is just one of about 10,000 children of incarcerated parents in Arlington, 100,000 in Virginia, and more than 2 million children in United States!

I started my organization, Children of Imprisoned Parents International (or COIPI) in 2014. After I met Arthur, and when he reminded me of my own personal experience once again, I decided to review our project to see how it could help to support him in order to start a new life with his mother. Our professional team, which includes Dr. Assari, who is an expert in public mental health on African American communities in the United States, Dr. Appleby, who is an expert on the design and management of facilitated programs and he has the added experience of working with Arlington county, as well as Ms. Chelante’, who has long term experience with at-risk children, have prepared a peer support facilitated program, to support caregivers or parents who experienced incarceration. Our experts, (and our program,) has helped children with incarcerated loved ones to deal with the inevitable trauma in a healthier way. The studies conducted behind programs like ours, has enabled us to be able to support caregivers and parents in order to make healthier communications and connections with their children. I have also looked at other programs that have existed in our community, such as: “Offender Aid and Restoration,” (OAR), has prepared prisoners, individuals who are coming back home from prison, and for children, specifically through their “Project Christmas Angel,” which engages our community to be part of the children’s, and their families’, lives.

Of course, there are other good programs in different cities, like in Fredrick, Maryland, where “Children of Incarcerated Parents Partnership” developed their projects, or in New York, where “Children of Promise” have some supportive programs for children with incarcerated parents, and also San Francisco County, where their school system has designed an educational and supportive program to prepare schools’ teachers, counselors, social workers and nurses to support children of incarcerated parents directly and individually.

All of these programs are based on academic research and show that healthy relationships between children and their incarcerated parents while they are in prison and after their release, play a significant role to keep our community safe. It keeps the prisoners – who are parents in their personal lives – avoid aggressive behavior while they are locked up. It helps the parents who have been released from prison, to avoid committing crimes and to keep them from coming back to prison once again. These programs also help their children to avoid risky behavior that may lead them to prison, like their parents, thus repeating the cycle.

Even though these programs have been proven to help, could they rebuild the broken relationship between child and parent that comes after the first moment that parent is locked up and physically taken from their child? From those first moments, a long-standing and sustainable connection must be made and kept between both parent and child. Although, I know in some cases there was a lack of communication between the children and parents before incarceration too, and this brings yet another challenge, the lack of parental knowledge. Of course, this is not applied to all of incarcerated parents.

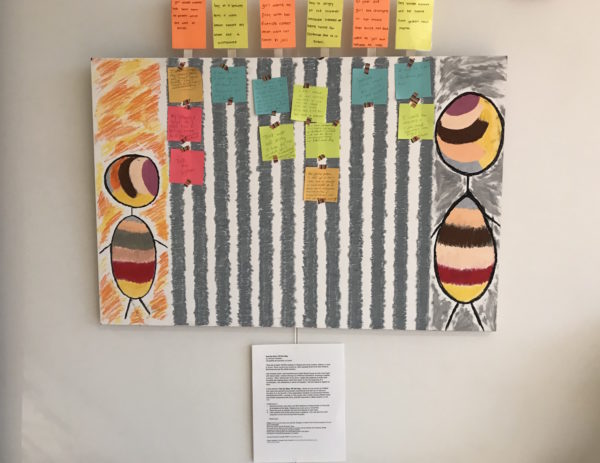

Now, this question brings another strategy to our organization. As long as we negotiate with other organizations to be partners with them and to run our peer support group program, we will advocate for children of incarcerated parents’ rights, as well as design and run community engagement programs to raise awareness about children whose parents are (or were) in prison. Last month when we started our interactive storytelling project in the Unitarian Universalist Church of Arlington, we had a chance to open a dialogue with community members who play different roles in those children’s lives, such as: teacher, neighbor, close family members or other caregivers. Studies have shown that the sustainable programs to support prisoner’s families are based on developing empathy between communities and families of incarcerated parents. Our community engagement projects focus on building and rebuilding empathy, and help all of us to put our services in a more sustainable foundation that will keep our community safer and to support our children in order to live to their highest level of development: free from negative consequences of parental incarceration. We plan to expand our interactive, dialogue based storytelling in different locations – including schools – and to keep our close relationships with other organizations to support our community. In the future, other than attending a summer camp for the third time, we are also partnering with a non-profit organization who’s focus is learning-entertainment opera programs. This nonprofit, “Opera Nova,” will run a free opera concert for children with incarcerated parents and military families in Arlington. We are also prepared for an international prisoners’ family conference in order to address one of the most challenging issues in children’s and returning parents’ lives: reunification. We do all these positive and important programs through partnering and working closely with other organizations in our area to give a vulnerable and unseen population a voice.

It was my pleasure to be here with you, and it is truly an honor to help serve our community.

Thank you for your time.